Jim Edgar

Jim Edgar | |

|---|---|

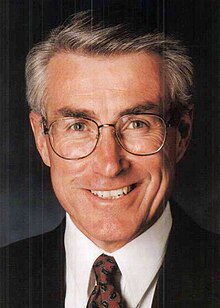

Edgar in 1993 | |

| 38th Governor of Illinois | |

| In office January 14, 1991 – January 11, 1999 | |

| Lieutenant | Bob Kustra (1991–1998) Vacant (1998–1999) |

| Preceded by | Jim Thompson |

| Succeeded by | George Ryan |

| 35th Secretary of State of Illinois | |

| In office January 12, 1981 – January 14, 1991 | |

| Governor | Jim Thompson |

| Preceded by | Alan J. Dixon |

| Succeeded by | George Ryan |

| Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from the 53rd district | |

| In office 1977–1979 Serving with Chuck Campbell and Larry Stuffle | |

| Preceded by | Max E. Coffey Bob Craig |

| Succeeded by | Harry Woodyard |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 22, 1946 Vinita, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Brenda Smith |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Eastern Illinois University |

| Website | Jim Edgar |

James Edgar (born July 22, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 38th governor of Illinois from 1991 to 1999.[1] A moderate Republican, Edgar previously served in the Illinois House of Representatives from 1976 to 1979 and as the 35th Secretary of State of Illinois from 1981 to 1991.[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Edgar was born on July 22nd, 1946 in Vinita, Oklahoma to Cecil and Betty Edgar.[3] Cecil, a small-businessman from Charleston, Illinois, died in an automobile accident in 1953, leaving Jim and his two older brothers to be raised by their mother.[4]

To support her children, Betty Edgar worked as a clerk at Eastern Illinois University, where Jim would later attend.[5] While at Eastern, Jim met his future wife Brenda Smith and served as student body president.[5] He graduated with a bachelor's degree in history in 1968.[3]

Edgar developed an interest in politics at a young age.[4] Though his parents were both Democrats, Edgar became a Republican while in elementary school after following the 1952 campaign of Dwight D. Eisenhower.[5][6]

A young Rockefeller Republican, Edgar briefly volunteered for the Presidential campaign of Pennsylvania Governor William Scranton in the 1964 Republican Primaries and supported New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller in 1968.[4][6]

Early political career

[edit]Work in the Illinois General Assembly

[edit]Following his graduation from college, Edgar served as a legislative intern and then personal assistant to Illinois Senate Republican leader W. Russell Arrington despite his mother's wish for him to attend law school.[4] Edgar would later regard the moderate Arrington as his role model.[4]

Following his time with Arrington, Edgar would also work briefly under Illinois House Speaker W. Robert Blair.[4]

Illinois House of Representatives

[edit]In 1974, Edgar ran unsuccessfully in the Republican nomination for state representative from the 53rd district, coming in third place.[7] After the campaign, Edgar worked as an insurance and cosmetics salesperson before briefly serving the National Conference of State Legislatures in Denver.[4]

He ran for the same seat again two years later in 1976 and won.[8] He was re-elected in 1978.[9]

While in the House, Edgar served on the Appropriations II, Human Resources, and Revenue committees as well as the Illinois Commission on Intergovernmental Cooperation.[10] Due to his moderate policy positions, Edgar was often considered a swing vote, especially on the Human Resources committee.[6]

In April 1979, shortly after winning re-election, Edgar resigned his state House seat to accept an appointment from Governor Jim Thompson to be the governor's legislative liaison.[4] Though reluctant at first, Edgar accepted Thompson's offer with an unwritten promise that it would lead to Edgar getting a spot on a statewide ticket later on.[6]

Illinois Secretary of State

[edit]In January 1981, Governor Thompson announced Edgar's appointment as Illinois Secretary of State to fill the vacancy left by incumbent Secretary of State Alan Dixon following his 1980 election to the U.S. Senate.[11] He won re-election twice in 1982 and 1986 with his 1986 re-election against the Illinois Solidarity Party nominee Jane N. Spirgel and the Lyndon LaRouche-backed Democratic nominee Janice A. Hart being the largest statewide margin of victory in Illinois history until the election of Barack Obama to the U.S. Senate in 2004.[12][13]

During his first term as Secretary of State, Edgar diverged from past practices in the office by keeping many of the Democratic employees hired by his predecessor.[14] He would later comment on his decision by saying "to me, the best politics is good government" and that in his view, as long as the employees did their jobs, he had no interest in firing them regardless of political affiliation.[14]

On policy, Edgar's partial term and first full term were largely defined by his work to toughen Illinois's drunk driving penalties.[4] This included strengthening breathalyzer requirements for individuals pulled over for possibly driving under the influence and reforming the state's legal view of driver's licenses to be a "privilege, not a right," thereby allowing licenses to be administratively suspended pending a court date for potentially driving drunk as opposed to the prior system where drivers retained their licenses until their court date.[14][15] Edgar also voiced support for a national 21-year-old legal drinking age and was appointed to U.S. President Ronald Reagan's Presidential Commission on Drunk Driving in 1982.[15]

During his second term, Edgar spearheaded a successful legislative battle to pass a bill instituting mandatory automobile insurance for Illinois motorists.[4][7] Prior to Edgar's intervention, the bill had been routinely defeated by the state's insurance lobby.[4] Edgar would later pick the Senate sponsor on the bill, Bob Kustra, to serve as his Lieutenant Governor.[4] Edgar also pushed forward an effort to construct a new Illinois State Library as its own building and his efforts to support the State Library during his tenure earned Edgar the nickname of "The Reader" from State Library employees.[7]

1990 Illinois gubernatorial election

[edit]On August 8th, 1989, Edgar announced his candidacy for Governor of Illinois following incumbent Governor Jim Thompson's decision not to run for a fifth term.[16] Despite instantly becoming the Republican Party's frontrunner and Thompson's heir-apparent, Edgar was challenged in the 1990 primary by minor candidate Robert Marshall and conservative activist Steve Baer.[17][18] Baer, the former executive director of the Illinois Republican Fund, opposed Edgar's pro-choice stance on abortion and his support of making permanent a then-temporary 20% income tax in support of the state's education system.[17] Edgar won the Republican nomination with a little under 63% of the primary vote.[19]

In the general election, Edgar faced Democrat Neil Hartigan, the incumbent Illinois Attorney General and former Illinois Lieutenant Governor under the state's last Democratic Governor Dan Walker.[20] Hartigan, like Baer, opposed making permanent the state's 20% education-focused income tax and attacked Edgar as a tax-and-spend politician.[17] Edgar, meanwhile, campaigned on fiscal responsibility for the state and on his character as a leader while attacking Hartigan as being an indecisive policy maker who changed his opinions on issues when it became politically convenient, a perspective that had hurt Hartigan in the past.[4][20][21] At one rally towards the end of the campaign, Edgar held up a waffle and joked that it would become the state seal if Hartigan were elected.[21]

Edgar's campaign was hindered by a poor national environment for Republicans and a desire amongst the Illinois public for a change in leadership following the previous four terms of Jim Thompson.[4][22] In the two weeks prior to the election, those hindrances paired with poor led Edgar to believe he was going to lose, but despite trailing Hartigan for most of election night, Edgar narrowly won the election by a little over 2% of the vote.[14][23] Edgar's victory occurred alongside the re-election of incumbent U.S. Senator Paul Simon in a Democratic landslide and made Edgar one of only two Republicans to win statewide office in Illinois that year.[24]

In the election's aftermath, a few factors were given credit for Edgar's success: first was his successful effort to market himself as a candidate representing change for the state despite being a Republican, second was the Edgar campaign's strong get-out-the-vote effort on election day, and third was Edgar's unique appeal to groups that were not traditionally a part of the state's Republican coalition.[4][24] Despite being attacked for it for most of the campaign, Edgar's position on the state income tax benefitted him with Chicago-area Black voters, many of whom already felt disrespected by Hartigan due to his endorsement of third party candidate Thomas Hynes in the 1987 Chicago Mayoral election against incumbent Democratic mayor Harold Washington, the city's first black mayor.[24][25][26] Also, during the campaign, Edgar openly opposed U.S. President George H.W. Bush's vetoing of the Civil Rights Act of 1990 and courted the support of prominent Black leaders, especially those involved with the recently-formed Harold Washington Party, gaining endorsements from many including Lu Palmer.[27][28][26] As a result, Edgar ran stronger in the Black community than any Republican had in decades, earning a quarter of the black vote in Cook County.[24][29] Edgar also performed better than Republicans traditionally did amongst Chicago's Latino voters, many of whom were already familiar with him thanks to Edgar's library and literacy programs while Secretary of State.[14][26] Edgar's gains amongst these traditionally Democratic groups helped negate his losses to Hartigan in more traditionally Republican areas of the state that would have otherwise resulted in a loss.[24][29] Reflecting on his victory later in life, Edgar would compare the coalition that elected him to Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition.[14]

Governor of Illinois

[edit]First term (1991–1995)

[edit]

On January 14th, 1991, Edgar took the oath of office as Governor of Illinois and gave a speech focused on fiscal responsibility.[30] During the gubernatorial transition between the 1990 election and his inauguration, Edgar and his staff were made aware of a nearly billion-dollar deficit in state spending that he would have to deal with upon assuming office and though the exact size of the deficit was downplayed by the Illinois State Bureau of the Budget to the public and to the news-media of the time, it was still recognized to be the largest budget deficit in state history up to that point.[31][32] Then, three weeks following Edgar's inauguration, the state began to feel stronger effects of the early 1990s recession, worsening the state's financial standing further.[33]

To try and correct the state's finances, Edgar's first proposed budget for the fiscal year 1992 included no tax increases and extensive cuts to state spending totaling in the millions of dollars—with the exception of education, which received a slight increase.[34][35] This budget ran into conflict with the Democrat-controlled Illinois General Assembly and a months-long budget fight ensued between Edgar and Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan over his proposals.[34][36] After months of negotiations, the two reached a compromise in mid-July that included most of Edgar's initial spending cuts, made permanent the temporary income tax increase that had dominated the 1990 campaign, and established property tax caps in all counties except Cook.[36][31] Edgar would have two more significant budget fights in 1992 and 1993 and the state's financial troubles would dominate much of Edgar's first term.[37][38]

In between budget fights, Edgar also sought to reform the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services, which had been put under court supervision following an ACLU lawsuit three years prior to Edgar taking office.[39] Policy changes enacted by Edgar included reorienting the department's priorities around focusing on the best interests of the children they were dealing with as opposed to keeping families together, toughening standards for private agencies and organizations overseeing child-care, and passing a bipartisan package of welfare reforms in 1994 focused on increasing scrutiny in abuse-related death investigations, establishing methods of stopping child abuse before it occurs, and requiring the department to draft standardized training procedures and guidelines for caseworkers.[39][40]

On April 24th, 1993, Edgar declared Kane, Lake, and McHenry counties disaster areas due to flooding.[31] This would be the first of many actions Edgar would take to curb the devastation of the Great Flood of 1993, later be regarded as one of the worst natural disasters in Illinois history.[31][41] Edgar would mobilize over 7,000 members of the Illinois National Guard to flood duty over the course of the disaster and organize hundreds of inmates from the Illinois Department of Corrections to help with sandbagging and levee-reinforcement.[42][31] Edgar would also help with sandbagging efforts himself throughout the summer.[41][31]

1994 Illinois gubernatorial election

[edit]In 1994, Edgar easily defeated Democratic comptroller Dawn Clark Netsch to win re-election.

Second term (1995–1999)

[edit]During his second term, the relationship between his re-election campaign and Management Systems of Illinois (MSI) came under federal scrutiny. MSI, Edgar's largest campaign contributor, was granted a contract that cost an estimated $20 million in overcharges. Edgar was never accused of wrongdoing, but he testified twice, once in court and once by videotape, becoming the first sitting Illinois governor to take the witness stand in a criminal case in 75 years. In those appearances, the governor insisted political donations played no role in who received state contracts.[43] Convictions were obtained against Management Services of Illinois; Michael Martin, who had been a partner of Management Services of Illinois; and Ronald Lowder, who had been a state welfare administrator and later worked for Management Services of Illinois.[44]

While pro-choice, Edgar signed into law the Parental Notification of Abortion Act during his second term.[45]

On August 20, 1997, Edgar announced he would retire from politics at the end of his second term. If he sought a third term, he was seen by his supporters as likely to win it. He was also encouraged by Republican officials to run for U.S. Senate that year, which he also declined to do.[46]

Edgar supported Secretary of State George Ryan to succeed him. Ryan was elected governor in 1998.[47]

"Edgar Ramp"

[edit]Prior to 1981, the State of Illinois funded pensions on an "as-you-go" basis, making benefit payouts as they came due, with employee contributions and investment income funding a reserve to cover future payouts. This approach was stopped in 1982 due to strains on the Illinois budget, and state contributions remained flat between 1982 and 1995, resulting in underfunding of pensions by approximately $20 billion. To address this shortfall, the Illinois legislature, in 1994, passed and then-Governor Edgar signed Public Act 88-593, which set payments by the State of Illinois into the pension funds at only 90 percent of liabilities, stretched this funding level over 50 years until 2045, and back-loaded payments with a 15-year ramp.[48] The underfunding of pension reserves over the first fifteen years was not fiscally sound, and was the major cause of a large gap between the State's obligations to pay pension benefits and the funds available to pay those benefits. As Governor, Edgar signed the pension legislation into law, and for this reason, the initial underfunding of pensions became known as the "Edgar Ramp."[49] The US Federal Securities and Exchange Commission described this analysis in a report.[50] Despite claims to the contrary, the gap in pension funding created by the Edgar Ramp had not been corrected as of June 2023,[51] with Illinois' public pensions being the worst-funded in the nation.[52]

Post-governorship

[edit]

Edgar is a distinguished fellow of the Institute of Government & Public Affairs at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.[53]

In 1999, Edgar was elected a fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration.[54]

Edgar was named the honorary chairman of the Ronald Reagan Centennial Celebration at Eureka College, President Reagan's alma mater. To open the Reagan Centennial year in January 2011, Governor Edgar delivered the keynote speech at the concluding dinner of the "Reagan and the Midwest" academic conference held at Eureka College.[55] In September 2011, Edgar helped dedicate the Mark R. Shenkman Reagan Research Center housed in the Eureka College library.[56]

As former chairman of the board of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation, Edgar underwrote the costs of the traveling trophy for the annual Lincoln Bowl tradition started in 2012. The Lincoln Bowl celebrates the Lincoln connection with Knox College and Eureka College, two Illinois colleges where Lincoln spoke, and is awarded to the winning team each time the two schools play each other in football.[57]

In July 2016, the Chicago Sun-Times reported that Illinois Financing Partners, a firm for which Edgar served as chairman, won approval by the state to advance money to state vendors who had been waiting for payments by the state. In turn, the firm would get to keep late payment fees when Illinois finally pays.[58]

Edgar was inducted as a Laureate of The Lincoln Academy of Illinois and awarded the Order of Lincoln (the State's highest honor) by the Governor of Illinois in 1999 in the area of Government.[59]

He is a resident fellow at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.[60]

Political opinions

[edit]A moderate Republican, Edgar supports abortion rights.[45]

In February 2008, Edgar endorsed Republican Senator John McCain of Arizona for President of the United States.[61]

Edgar supported Mitt Romney in 2012.[62] When Donald Trump won the Republican nomination in 2016, Edgar publicly announced that he would not be voting for the candidate.[63] After the President's second nomination, Edgar, along with other Illinois GOP moderates, announced their support of former United States Vice President and Democratic challenger Joe Biden.[64] Edgar told Peoria-area newspaper Peoria Journal Star, "I have been very disappointed. We’ve had chaos for four years we didn’t need to have. I mean, there’s always going to be some turmoil, but he stirs it up. He bullies. You can’t believe what he says because he’ll do the different thing the next day. ... He’s bungled the virus, there’s no doubt about that. He continued to stir up division in the country, (when) a president should be trying to bring people together. I mean, the list goes on and on."[65]

In the spring of 2016, Edgar said that he believed Governor Bruce Rauner should sign the Democratic budget and support the Democratic pension plan.[66] Edgar pushed for a pension bill to save $15 billion back in 1994.[67] "We had a time bomb in our retirement system that was going to go off in the first part of the 21st century," Edgar told The State Journal-Register in 1994. "This legislation defuses that time bomb."[67] The legislature passed Edgar's bill unanimously.[67]

Personal life

[edit]Edgar is married to Brenda Smith Edgar. They have two children, Brad and Elizabeth.[4]

In 1994, Edgar underwent emergency quadruple bypass surgery and was hospitalized in 1998 for chest pains.[68]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Illinois Governor Jim Edgar". Governor's Information. National Governors Association. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- ^ Howard, Robert (1999). Mostly Good and Competent Men (2nd ed.). University of Illinois at Springfield, Center for State Policy and Leadership. pp. 332–333. ISBN 978-0938943150.

- ^ a b "Jim Edgar". National Governors Association. January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Jim Edgar, Illinois' 38th governor". www.lib.niu.edu. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Early Years | Jim Edgar". Retrieved August 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Oral History Interview with Jim Edgar Volume I". Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

- ^ a b c Illinois State Library Heritage Project (January 20, 2023). "Jim Edgar". The Official Website for the Illinois Secretary of State. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ "Our Campaigns - IL State House 053 Race - Nov 02, 1976".

- ^ "Our Campaigns - IL State House 053 Race - Nov 07, 1978".

- ^ State of Illinois (August 1978). Illinois Blue Book, 1977-1978. State of Illinois. pp. 66–67, 188.

- ^ "pg. 34- Illinois Issues, January, 1981". www.lib.niu.edu. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

- ^ "Illinois blue book, 1997-1998 :: Illinois Blue Books". Idaillinois.org. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ Christopher Wills (November 3, 2004). "Commuters give Obama the thumbs-up". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f "Oral History Interview with Jim Edgar Volume II". Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.

- ^ a b Borysowicz, Joseph (October 3, 1983). "Edgar seeks tougher law". Daily Vidette. pp. 1, 9.

- ^ "Edgar keeping track of more than time". The Chicago Tribune. August 10, 1989.

- ^ a b c Schmidt, William E.; Times, Special To the New York (March 12, 1990). "New Faces in Primary For Governor of Illinois". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "GOP leadership in the '90s: a primary challenge". www.lib.niu.edu. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "State of Illinois official vote cast at the primary election held on ..." Illinois State Board of Elections. 1990. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Levinsohn, Florence Hamlish (October 25, 1990). "What's the Deal With Neal Hartigan?". Chicago Reader. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "Edgar bashes Hartigan in waffle stunt". The Chicago Tribune. November 5, 1990.

- ^ Jr, R. W. Apple (November 8, 1990). "The 1990 Elections: Signals - The Message; The Big Vote Is for 'No'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "State of Illinois official vote cast at the general election ." Illinois State Board of Elections. 1991. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Edgar squeaks past Hartigan". The Chicago Tribune. November 7, 1990.

- ^ "Hynes withdraws from mayoral race - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c Broder, David S. (October 29, 1990). "A 'D-Word' Spells Trouble for Black Democrats in Illinois Campaign". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ Guy, Sandra (July 12, 1990). "Black activists endorse Jim Edgar". nwitimes.com. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ Reports, Staff (September 25, 1994). "Black voters get less of Edgar's time". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "Vote analysis of Edgar victory:". www.lib.niu.edu. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "Edgar takes helm in Illinois". Chicago Tribune. January 15, 1991. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Oral History Interview with Governor Jim Edgar Vol III". Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

- ^ "Hon. Jim Edgar and Robin Steans - City Club of Chicago". www.cityclub-chicago.org. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ @ilpublicmedia (June 25, 2015). "Former Governor Sees Parallels From 1991 To Current Budget Impasse". Illinois Public Media. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ a b KLEMENS, MICHAEL D. "The state of the state: Democratic dilemma in reconfiguring Edgar's budget". www.lib.niu.edu. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ Tribune, Chicago (April 10, 1991). "EDGAR WARNS OF DEEPER BUDGET CUTS". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ a b @ilpublicmedia (June 25, 2015). "Former Governor Sees Parallels From 1991 To Current Budget Impasse". Illinois Public Media. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ "Jim Edgar administration to be subject of conference in Springfield". The Holland Sentinel. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ Content, Contributed (November 9, 1994). "JIM EDGAR'S BIG VICTORY". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ a b "Children & Families | Jim Edgar". Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ Tribune, Chicago (June 16, 1994). "CHILD-WELFARE REFORMS NOW IN EDGAR'S HANDS". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Tribune, Chicago; Garcia, Monique (April 23, 2013). "Governor wades into spotlight during flooding". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ "Remembering the Great Flood of 1993: 30 Years Later". Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ "Msi Scandal Link To Aides Of Edgar, Philip Revealed - tribunedigital-chicagotribune". Articles.chicagotribune.com. August 24, 2000. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ "Illinois Campaign Donor Is Convicted of Bribery". The New York Times. Associated Press. August 17, 1997 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ a b "The Jim Edgar Interview: Illinois' former governor looks back on his legacy, offers advice to GOP hopefuls". WCIA.com. November 29, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "Washingtonpost.com: Gephardt, Still Leading With His Left". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ https://www.facebook.com/nationalgovernorsassociation (January 12, 2015). "George H. Ryan". National Governors Association. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); External link in|last= - ^ Brown, Jeffrey R; Dye, Richard F (June 1, 2015). "Illinois Pensions in a Fiscal Context: A (Basket) Case Study". Working Paper Series. doi:10.3386/w21293 – via National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ^ Zorn, Eric (June 14, 2016). "The 'Edgar Ramp' took Illinois downhill, but many share the blame". chicagotribune.com.

- ^ "Administrative proceeding" (PDF). www.sec.gov. March 11, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ https://www.chicagobusiness.com/greg-hinz-politics/sp-ratings-says-illinois-still-shortchanges-pensions.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Nates-Perez, Alex (August 24, 2023). "Unfunded Liabilities for State Pension Plans in 2023". Equable.

- ^ "Jim Edgar". Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois: Institute of Government and Public Affairs. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ Incorporated, Prime. "National Academy of Public Administration". National Academy of Public Administration. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Steinbacher, Michele (November 23, 2010). "Edgar, Meese to appear at Reagan conference in Eureka". Pantagraph.com. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ Chris Kaergard (September 26, 2011). "Edgar dedicates Mark R. Shenkman Reagan Research Center - News - Woodford Times - Peoria, IL - Metamora, IL". Woodford Times. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ "Lincoln Bowl". Pantagraph.com. September 2, 2013. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ Fusco, Chris; Novak, Tim (July 2, 2016). "WATCHDOGS: Ex-Gov. Jim Edgar aims to cash in on state's cash woes". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ "Laureates by Year - The Lincoln Academy of Illinois". The Lincoln Academy of Illinois. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ "Edgar Fellow Program – IGPA". Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ Tackett, Michael (February 1, 2008). "Former Ill. Gov. Edgar endorses McCain". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ "Edgar: GOP Campaign Has Gone On Too Long « CBS Chicago". Chicago.cbslocal.com. March 21, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ Petrella, Dan (September 28, 2016). "Edgar: Trump candidacy, Rauner money make 2016 unpredictable". pantagraph.com.

- ^ McKinney, Dave (August 24, 2020). "Former Gov. Edgar And Other Moderate Illinois Republicans Say They'll Vote For Joe Biden". WBEZ. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Schoenburg, Bernard. "Former GOP Gov. Edgar says he'll vote for Biden". PJ Star.

- ^ Glennon, Mark (October 20, 2015). "Why Jim Edgar Has Zero Credibility on Illinois Budget, Pensions: It's Not Just the 'Edgar Ramp' – WP Original | Wirepoints".

- ^ a b c "The Edgar ramp – the 'reform' that unleashed Illinois' pension crisis". Illinois Policy. October 27, 2015.

- ^ "GOV. EDGAR'S HEART SURGERY SUCCESSFUL". Chicago Tribune. July 8, 1994. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Gov. Edgar reacts to the allegations against Gov. Rod Blagojevich – link to speech, op-ed, and interview about the 2008–2009 Blagojevich scandal; from the University of Illinois Institute of Government and Public Affairs

- Appearances on C-SPAN