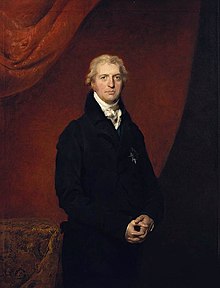

Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

The Earl of Liverpool | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 8 June 1812 – 9 April 1827 | |

| Monarchs | |

| Regent | George, Prince Regent (1812–1820) |

| Preceded by | Spencer Perceval |

| Succeeded by | George Canning |

| Secretary of State for War and the Colonies | |

| In office 1 November 1809 – 11 June 1812 | |

| Prime Minister | Spencer Perceval |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Castlereagh |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Bathurst |

| Leader of the House of Lords | |

| In office 25 March 1807 – 9 April 1827 | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | The Lord Grenville |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Goderich |

| In office 17 August 1803 – 5 February 1806 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | The Lord Pelham |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Grenville |

| Home Secretary | |

| In office 25 March 1807 – 1 November 1809 | |

| Prime Minister | The Duke of Portland |

| Preceded by | The Earl Spencer |

| Succeeded by | Richard Ryder |

| In office 12 May 1804 – 5 February 1806 | |

| Prime Minister | William Pitt the Younger |

| Preceded by | Charles Philip Yorke |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Spencer |

| Foreign Secretary | |

| In office 20 February 1801 – 14 May 1804 | |

| Prime Minister | Henry Addington |

| Preceded by | The Lord Grenville |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Harrowby |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Banks Jenkinson 7 June 1770 London, England |

| Died | 4 December 1828 (aged 58) Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, England |

| Resting place | Hawkesbury Parish Church, Gloucestershire, England |

| Political party | Tory |

| Spouses | |

| Parent | Charles Jenkinson (father) |

| Education | Charterhouse School |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

| Signature | |

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, KG, PC, FRS (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1827. He also held many other important cabinet offices such as Foreign Secretary, Home Secretary and Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. He was also a member of the House of Lords and served as leader.

As prime minister, Jenkinson called for repressive measures at domestic level to maintain order after the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. He dealt smoothly with the Prince Regent when King George III was incapacitated. He also steered the country through the period of radicalism and unrest that followed the Napoleonic Wars. He favoured commercial and manufacturing interests as well as the landed interest. He sought a compromise of the heated issue of Catholic emancipation. The revival of the economy strengthened his political position. By the 1820s, he was the leader of a reform faction of "Liberal Tories" who lowered the tariff, abolished the death penalty for many offences, and reformed the criminal law. By the time of his death, however, the Tory party, which had dominated the House of Commons for over 40 years, was ripping itself apart.

Important events during his tenure as prime minister included the War of 1812 with the United States, the Sixth and Seventh Coalitions against the French Empire, the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars at the Congress of Vienna, the Corn Laws, the Peterloo Massacre against pro-democracy protestors, the Trinitarian Act 1812 and the emerging issue of Catholic emancipation.

Early life

[edit]Jenkinson was born on 7 June 1779, the son of politician Charles Jenkinson, later the first Earl of Liverpool, and his first wife, Amelia Watts. Jenkinson's 19-year-old mother, who was the daughter of senior East India Company official William Watts and his wife Frances Croke, died one month after his birth.[1] Through his mother's maternal grandmother, Isabella Beizor, Jenkinson was descended from Portuguese settlers in India and he may also have had Indian ancestors.[2]: 10 He was baptised on 29 June 1770 at St. Margaret's, Westminster.[1]

Jenkinson's father would not remarry until 1782 and as a small child Jenkinson was looked after by his widowed paternal grandmother, Amarantha Jenkinson, in Winchester. His maternal aunt, Sophia Watts, and his paternal aunt Elizabeth, wife of Charles Wolfran Cornwall, were also involved in his early years. He briefly attended schools in Winchester and Chelsea before starting, aged nine, at Albion House preparatory school in Parsons Green.[2]: 24-25

When he was thirteen, Jenkinson became a boarder at his father's old school, Charterhouse School, under the headmaster Samuel Berdmore. His father had ambitions of high office for him and exhorted him in letters to apply himself not just to his studies, but also to his appearance and personal habits.[1][2]: 27 From Charterhouse, he went up to Christ Church, Oxford in April 1787. At university he was a sober and hardworking student. He formed what was to be a lifelong friendship with George Canning, although at times they would be political rivals. Together with a few other students, including Lord Henry Spencer, they set up a debating society where Jenkinson would present the Tory and Canning the Whig point of view. Having spent a summer in Paris, where he witnessed the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1798, Jenkinson was created a Master of Arts at Oxford in May 1790.[1][2]: 31

Early career (1790–1812)

[edit]Member of Parliament

[edit]Jenkinson's political career began when he was elected to two seats in the 1790 general election, Rye and Appleby. He chose to represent the former, and never sat for Appleby. Still under age when he was elected, he spent several months touring Continental Europe and did not take up his seat for Rye until after his twenty-first birthday, near the end of the 1791 session.[1][2]: 40 He made his maiden speech in February 1792, giving the government's reply to Samuel Whitbread's critical motion on the government's foreign policy. The Times praised it as "able and learned; cloathed in the best language and delivered with all the powers and graces of oratory". Several speeches followed, including one opposing William Wilberforce's motion to abolish the slave trade and one in opposition to an inquiry into the Birmingham riots[2]: 40-44 After the 1792 parliamentary session ended in June, Jenkinson travelled to Koblenz, which was a centre for French émigrés. French newspapers accused him of being an agent of the government; The Times denied the rumours.[1][2]: 44 His services as a capable speaker for the government were recognised in 1793 when he was appointed to the India Board.[2]: 48-49

After the outbreak of hostilities with France, Jenkinson joined the militia and in 1794 became a colonel in the Cinque Ports Fencibles.[1] There was a rare conflict between Jenkinson and his father when he fell in love with Lady Louisa Hervey, daughter of the Earl of Bristol and wife Elizabeth Davers. Lord Bristol approved of the match and offered a £10,000 dowry, but Jenkinson's father though that Jenkinson should not marry before he was thirty unless it was to a fortune. He also objected to the Hervey family's eccentricity and Whig connections, only relenting after the intervention of Pitt and George III. The couple married on 25 March 1795 at Wimbledon.[1][2]: 51-53 Jenkinson's father was created Earl of Liverpool in May 1796, bringing Jenkinson the courtesy title of Lord Hawkesbury.[2]: 51-54 The Cinque Ports Fencibles were posted to Scotland, where they provided a guard for the funeral of Robert Burns in 1796 and took part in suppressing riots near Dunbar in 1797.[2]: 51,54 .

In March 1799 he became a privy councillor, member of the Board of Trade and master of the Royal Mint.[3]

Cabinet

[edit]Foreign Secretary and Home Secretary

[edit]Hawkesbury, as he now was, obtained his first cabinet position in 1801 when he became Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in Henry Addington's administration and was responsible for negotiating the Treaty of Amiens with France. In 1803 he was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Hawkesbury in order to support the government against Lord Grenville's attacks.[1] When Pitt returned to power in May 1804, Hawkesbury became Home Secretary and leader of the House of Lords. After Pitt's death in January 1806, the king asked Hawkesbury to form a government but he refused and instead was awarded the lucrative sinecure of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. Following the resignation of Grenville in March 1807, Hawkesbury advised the king to ask the Duke of Portland to form a ministry and returned to his role as Home Secretary. In December 1808, on the death of his father, Hawkesbury became Lord Liverpool.[1]

War Secretary

[edit]Liverpool accepted the position of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies when Spencer Perceval formed a ministry in November 1809. During his time in office, he ensured that the cabinet gave sufficient support to the Peninsular War.[1] In 1810, he was made a colonel of militia.[3]

Prime minister (1812–1827)

[edit]Appointment

[edit]After the Assassination of Spencer Perceval in May 1812, George, the Prince Regent, successively tried to appoint four men to succeed Perceval, but failed. Jenkinson, the Prince Regent's fifth choice for the post, reluctantly accepted office on 8 June 1812.[4][5] Jenkinson was proposed as successor by the cabinet office and Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh who acted as leader in the House of Commons. The Prince Regent, however, found it impossible to form a different coalition to advance an alternative candidate and confirmed Jenkinson as prime minister on 8 June.

The Liverpool government

[edit]Liverpool's government included some of the future leaders of Britain, such as Lord Castlereagh, George Canning, the Duke of Wellington, Robert Peel, and William Huskisson. Liverpool was considered an experienced and skilled politician, and held together the liberal and reactionary wings of the Tory party, which his successors, Canning, Goderich and Wellington, had great difficulty with.[citation needed]

War

[edit]Congress of Vienna

[edit]

Liverpool's ministry was a long and eventful one. At the beginning of his premiership, Liverpool was faced directly with conflict, the War of 1812 with the United States and the final campaigns of the Napoleonic Wars were fought during Liverpool's governance. It was during his ministry that the Peninsular Campaigns were fought, where the British army led by the Duke of Wellington drove the French out of Spain and Portugal that lasted six years. France was utterly defeated in the Napoleonic Wars, and Liverpool was appointed to the Order of the Garter that same year. At the peace negotiations that followed, Liverpool's main concern was to obtain a European settlement that would ensure the independence of the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal, and confine France inside its pre-war frontiers without damaging its national integrity. To achieve this, he was ready to return all British colonial conquests. Within this broad framework, he gave Castlereagh a discretion at the Congress of Vienna, the next most important event of his ministry. At the congress, he gave prompt approval for Castlereagh's bold initiative in making the defensive alliance with Austria and France in January 1815. In the aftermath of the defeat of Napoleon – who had briefly been exiled to the island Elba, but had escaped exile and returned to rule France. The allies immediately began mobilising their armies to fight the escaped emperor and a combined Anglo-Allied army was sent under the command of Wellington to assist Britain's allies. Within a few months, Napoleon was decisively defeated at Waterloo in June that year, after many years of war, peace followed through the now exhausted continent.

The Corn Laws

[edit]Home trouble

[edit]Inevitably taxes rose to compensate for borrowing and to pay off the national debt, which led to widespread disturbance between 1812 and 1822. Around this time, the group known as Luddites began industrial action, by smashing industrial machines developed for use in the textile industries of the West Riding of Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire. Throughout the period 1811–1816, there was a series of incidents of machine-breaking and many of those convicted faced execution.[6]

Agriculture remained a problem because good harvests between 1819 and 1822 had brought down prices and evoked a cry for greater protection. When the powerful agricultural lobby in Parliament demanded protection in the aftermath, Liverpool gave in to political necessity. Under governmental supervision the notorious Corn Laws of 1815 were passed prohibiting the import of foreign wheat until the domestic price reached a minimum accepted level. Liverpool, however, was in principle a free-trader, but had to accept the bill as a temporary measure to ease the transition to peacetime conditions. His chief economic problem during his time as Prime Minister was that of the nation's finances.[citation needed]

The interest on the national debt, massively swollen by the enormous expenditure of the final war years, together with the war pensions, absorbed the greater part of normal government revenue. The refusal of the House of Commons in 1816 to continue the wartime income tax left ministers with no immediate alternative but to go on with the ruinous system of borrowing to meet necessary annual expenditure. Liverpool eventually facilitated a return to the gold standard in 1819.[citation needed]

Liverpool argued for the abolition of the wider slave trade at the Congress of Vienna, and at home he supported the repeal of the Combination Laws banning workers from combining into trade unions in 1824.[7] In the latter year the newly formed Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck, later the RNLI, obtained Liverpool as its first president.[8]

Assassination attempt

[edit]

The reports of the secret committees he obtained in 1817 pointed to the existence of an organised network of disaffected political societies, especially in the manufacturing areas. Liverpool told Peel that the disaffection in the country seemed even worse than in 1794. Because of a largely perceived threat to the government, temporary legislation was introduced. He suspended habeas corpus in both Great Britain (1817) and Ireland (1822). Following the Peterloo Massacre in 1819, his government imposed the repressive Six Acts legislation which limited, among other things, free speech and the right to gather for peaceful demonstration. In 1820, as a result of these measures, Liverpool and other cabinet ministers were targeted for assassination. They escaped harm when the Cato Street conspiracy was foiled.[9]

Catholic emancipation

[edit]During the 19th century, and, in particular, during Liverpool's time in office, Catholic emancipation was a source of great conflict. In 1805, in his first important statement of his views on the subject, Liverpool had argued that the special relationship of the monarch with the Church of England, and the refusal of Roman Catholics to take the oath of supremacy, justified their exclusion from political power. Throughout his career, he remained opposed to the idea of Catholic emancipation, though he did see marginal concessions as important to the stability of the nation.

The decision of 1812 to remove the issue from collective cabinet policy, followed in 1813 by the defeat of Grattan's Roman Catholic Relief Bill, brought a period of calm. Liverpool supported marginal concessions such as the admittance of English Roman Catholics to the higher ranks of the armed forces, the magistracy, and the parliamentary franchise; but he remained opposed to their participation in parliament itself. In the 1820s, pressure from the liberal wing of the Commons and the rise of the Catholic Association in Ireland revived the controversy.

By the date of Sir Francis Burdett's Catholic Relief Bill in 1825, emancipation looked a likely success. Indeed, the success of the bill in the Commons in April, followed by Robert Peel's tender of resignation, finally persuaded Liverpool that he should retire. When Canning made a formal proposal that the cabinet should back the bill, Liverpool was convinced that his administration had come to its end. George Canning then succeeded him as prime minister. Catholic emancipation however was not fully implemented until the major changes of the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 under the leadership of the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel, and with the work of the Catholic Association established in 1823.[10]

Retirement and death

[edit]Jenkinson's first wife, Louisa, died at 54. He married again on 24 September 1822 to Mary Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool.[11] Jenkinson finally retired on 9 April 1827 after suffering a severe cerebral hemorrhage at his Fife House residence in Whitehall two months earlier,[12] and asked the King to seek a successor. He suffered another minor stroke in July, after which he lingered on at Coombe, Kingston upon Thames until a third attack on 4 December 1828 from which he died.[13] Having died childless, he was succeeded as Earl of Liverpool by his younger half-brother Charles Jenkinson, 3rd Earl of Liverpool. Jenkinson was buried in Church of St Mary, Hawkesbury beside his father and his first wife.

Legacy

[edit]Robert William Seton-Watson sums up Jenkinson's strengths and weaknesses:

No one would claim Liverpool as a man of genius, but he had qualities of tact, firmness and endurance to which historians have rarely done full justice: and thus it came about that he held the office of Premier over a period more than twice as long as any other successor of Pitt, long after peace had been restored to Europe. One reason for his ascendancy was that he had an unrivalled insight into the whole machinery of government, having filled successively every Secretaryship of State, and tested the efficiency and mutual relations of politicians and officials alike.... He had a much wider acquaintance with foreign affairs than many who have held his high office.[14]

John W. Derry says Jenkinson was:

[A] capable and intelligent statesman, whose skill in building up his party, leading the country to victory in the war against Napoleon, and laying the foundations for prosperity outweighed his unpopularity in the immediate post-Waterloo years.[15]

Jenkinson was the first British prime minister to regularly wear long trousers instead of breeches. He entered office at the age of 42 years and one day, making him younger than all of his successors. Liverpool served as prime minister for a total of 14 years and 305 days, making him the longest-serving prime minister of the 19th century. As of 2023, none of Liverpool's successors has served longer.

In London, Liverpool Street and Liverpool Road, Islington, are named after Lord Liverpool. The Canadian town of Hawkesbury, Ontario, the Hawkesbury River and the Liverpool Plains, New South Wales, Australia, Liverpool, New South Wales, and the Liverpool River in the Northern Territory of Australia were also named after Lord Liverpool.[16]

Lord Liverpool, as Prime Minister to whose government Nathan Mayer Rothschild was a lender, was portrayed by American actor Gilbert Emery in the 1934 film The House of Rothschild.

Lord Liverpool's ministry (1812–1827)

[edit]

- Lord Liverpool – First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Lords

- Lord Eldon – Lord Chancellor

- Lord Harrowby – Lord President of the Council

- Lord Westmorland – Lord Privy Seal

- Lord Sidmouth – Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Castlereagh (Lord Londonderry after 1821) – Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the House of Commons

- Lord Bathurst – Secretary of State for War and the Colonies

- Lord Melville – First Lord of the Admiralty

- Nicholas Vansittart – Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Lord Mulgrave – Master-General of the Ordnance

- Lord Buckinghamshire – President of the Board of Control

- Charles Bathurst – Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Lord Camden – minister without portfolio

Changes

[edit]- Late 1812 – Lord Camden leaves the Cabinet

- September 1814 – William Wellesley-Pole (Lord Maryborough from 1821), the Master of the Mint, enters the Cabinet

- February 1816 – George Canning succeeds Lord Buckinghamshire at the Board of Control

- January 1818 – F. J. Robinson, the President of the Board of Trade, enters the Cabinet

- January 1819 – The Duke of Wellington succeeds Lord Mulgrave as Master-General of the Ordnance. Lord Mulgrave becomes minister without portfolio

- 1820 – Lord Mulgrave leaves the cabinet

- January 1821 – Charles Bathurst succeeds Canning as President of the Board of Control, remaining also at the Duchy of Lancaster

- January 1822 – Robert Peel succeeds Lord Sidmouth as Home Secretary

- February 1822 – Charles Williams-Wynn succeeds Charles Bathurst at the Board of Control. Bathurst remains at the Duchy of Lancaster and in the Cabinet

- September 1822 – Following the suicide of Lord Londonderry, George Canning becomes Foreign Secretary and Leader of the House of Commons

- January 1823 – Vansittart, elevated to the peerage as Lord Bexley, succeeds Charles Bathurst as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. F. J. Robinson succeeds Vansittart as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He is succeeded at the Board of Trade by William Huskisson

- 1823 – Lord Maryborough, the Master of the Mint, leaves the Cabinet. His successor in the office is not a Cabinet member

Arms

[edit]

|

|

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Jenkinson, Robert Banks, second earl of Liverpool (1770-1828)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14740. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hay, William Anthony (2018). Lord Liverpool. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978 1 78327 282 2.

- ^ a b Thorne, R.G. (1986). "Jenkinson, Hon. Robert Banks (1770-1828), of Coombe Wood, nr. Kingston, Surr". History of Parliament.

- ^ Marjie Bloy (4 March 2002). "Lord Liverpool". The Victorian Web.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ "Lord Liverpool". Victorian Web. 4 March 2002.

- ^ W. R. Brock (1967). Lord Liverpool and Liberal Toryism 1820 to 1827. CUP Archive. p. 3.

- ^ Lewis, Richard (1874). "History of the life-boat, and its work". MacMillan & Co. Retrieved 8 December 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Ann Lyon (2003). Constitutional History of the UK. Routledge. p. 319. ISBN 978-1-135-33700-1.

- ^ Richard W. Davis, "Wellington and the 'Open Question': The Issue of Catholic Emancipation, 1821–1829", Albion, (1997) 29#1 pp 39–55. doi:10.2307/4051594

- ^ Gash, Norman (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 29. Oxford University Press. p. 988. ISBN 978-0-19-861379-4.

- ^ "Robert Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool". Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ "Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Edinburgh. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ R. W. Seton-Watson, Britain in Europe (1789–1914): A Survey of Foreign Policy (1937) (1937), p. 29.

- ^ John Cannon, ed. (2009). The Oxford Companion to British History. p. 582.[ISBN missing]

- ^ "Place Names Register Extract – Liverpool River". NT Place Names Register. Northern Territory Government. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Brock, W. R. (1943). Lord Liverpool and Liberal Toryism 1820 to 1827. CUP Archive. p. 2.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 804. This contains an assessment of his character and achievements.

- Cookson, J. E. Lord Liverpool's administration: the crucial years, 1815–1822 (1975)

- Gash, Norman. Lord Liverpool: The Life and Political Career of Robert Banks Jenkinson, Second Earl of Liverpool 1770–1828 (1984)

- Gash, Norman. "Jenkinson, Robert Banks, second earl of Liverpool (1770–1828)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004); online ed. 2008 accessed 20 June 2014 doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14740

- Gash, Norman. "Lord Liverpool: a private view," History Today (1980) 30#5 pp 35–40

- Hilton, Boyd. A Mad, Bad, and Dangerous People? England 1783–1846 (New Oxford History of England) (2006) scholarly survey

- Hilton, Boyd. "The Political Arts of Lord Liverpool." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (Fifth Series) 38 (1988): 147–170. online

- Hutchinson, Martin. Britain's Greatest Prime Minister: Lord Liverpool (Cambridge, The Lutterworth Press, 2020).

- Petrie, Charles. Lord Liverpool and His Times (1954)

- Plowright, John. Regency England: The Age of Lord Liverpool (Routledge, 1996) "The Lancaster Pamphlets".

- Sack, James J. The Grenvillites, 1801–29: Party Politics and Factionalism in the Age of Pitt and Liverpool (1991)

- Seton-Watson, R. W. Britain in Europe (1789–1914): A Survey of Foreign Policy (1937) online free

External links

[edit]- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl of Liverpool

- Earl of Liverpool Prime Minister's Office (archived 12 November 2008)

- "Earl of Liverpool" by Prime Minister's Office (archived 12 November 2008)

- Portraits of Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- "Archival material relating to Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool". UK National Archives.

- Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

- 1770 births

- 1828 deaths

- 19th-century prime ministers of the United Kingdom

- Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford

- British MPs 1790–1796

- British MPs 1796–1800

- British Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs

- Earls of Liverpool (1796 creation)

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Knights of the Garter

- Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports

- Masters of the Mint

- Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies

- Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies

- People educated at Charterhouse School

- People from Westminster

- Secretaries of State for the Home Department

- Secretaries of State for War and the Colonies

- Tory MPs (pre-1834)

- UK MPs 1801–1802

- UK MPs 1802–1806

- UK MPs who inherited peerages

- Commissioners of the Treasury for Ireland

- Tory prime ministers of the United Kingdom

- Leaders of the House of Lords

- British people of Indian descent

- British people of Portuguese descent

- Deaths from cerebrovascular disease