1997 Jarrell tornado

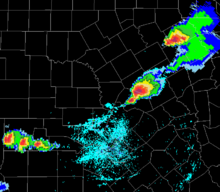

Counterclockwise from top: The tornado at F5 intensity before striking the Double Creek Estates, the radar scan showing the tornado, an aerial view of the tornado track at Double Creek Estates and a mangled car in Jarrell. | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | May 27, 1997, 3:40 pm. CDT (UTC−05:00) |

| Dissipated | May 27, 1997, 3:53 pm. CDT (UTC−05:00) |

| Duration | 13 minutes |

| F5 tornado | |

| on the Fujita scale | |

| Highest winds | >261 mph (420 km/h) |

| Highest gusts | 261 mph (420 km/h) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 27 |

| Injuries | 12 |

| Damage | $40.1 million (1997 USD) |

| Areas affected | Jarrell, Texas and areas near Prairie Dell, Texas |

Part of the 1997 Central Texas tornado outbreak and tornadoes of 1997 | |

The 1997 Jarrell tornado was an exceptionally violent and destructive multi-vortex tornado that struck the community of Jarrell, Texas in the afternoon hours of May 27, killing 27 people and injuring a further 12.[1] The tornado caused $40.1 million (1997 USD) in damages, and was the subject of multiple well-known photographs, earning the tornado the nickname of the "Dead Man Walking".[2]

The tornado stalled over the Double Creek Estates housing subdivision for approximately 3 minutes at high-end F5 strength, causing arguably some of the most severe tornado damage ever recorded. NIST Studies on the tornado have been conducted in the years and decades after the event.[3]

As of 2024, this tornado is Texas' most recent F5 or EF5 tornado.[4] The tornado was the fourth-deadliest of the 1990s in the United States, only being surpassed by the 1990 Plainfield tornado that killed 29, the 1998 Birmingham tornado that killed 32, and the 1999 Bridge Creek–Moore tornado that killed 36. It was also the only F5 tornado of 1997, and the next F5 would occur on April 8 of the following year.

Meteorological synopsis

[edit]

On the morning of May 27, 1997, an upper-level low-pressure area located over portions of South Dakota and Nebraska lifted north, causing a weak, mid-level flow across Texas as a result. While this occurred, a cold front extended southwest of a surface-based low-pressure area from Fayetteville, Arkansas to the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex to the Permian Basin, which also included two decaying outflow boundaries northeast of the DFW metroplex. A gravity wave was also noted from the cold front near Waco, Texas and southward, which would promote initiation of supercells, including the one which produced the Jarrell tornado.[5] The latter two factors were caused by an overnight mesoscale convective system which had dissipated before the mesoscale setup of the Jarrell tornado.[6]

An upper-air balloon sounding was conducted by the National Weather Service in Fort Worth while the cold front passed directly over the DFW metroplex, which showed favorable mid-level lapse rates, a dewpoint temperature of 73 °F (23 °C) on the surface, and some wind shear, though not towards the surface, which suggested non-tornadic supercell activity. However, a sounding launched from Calvert, Texas a few hours later revealed surface-based convective available potential energy (CAPE) values above 6500 j/kg, up from 3000 j/kg shown by the sounding previously launched over the DFW metroplex.[5] This, along with extremely high CAPE values shown near the surface from a sounding over Waco at 12:00 CDT (17:00 UTC), likely caused vorticity near and along the cold front and the production of the Jarrell tornado.[5]

The supercell that produced the Jarrell tornado first began to develop in McLennan County prior to noon, initially moving slowly southwestward in the unstable airmass. Shortly thereafter, a tornado watch was issued by the Storm Prediction Center for eastern Texas and western Louisiana. As the thunderstorm cell moved parallel to Interstate 35, it rapidly intensified and prompted the issuance of a Severe Thunderstorm Warning for portions of McLennan County at 12:50 CDT (17:50 UTC), later being upgraded to a Tornado Warning as the supercell then began to rapidly exhibit lower-levels of rotation. This would result in multiple tornadoes being produced before the Jarrell tornado occurred; most notably an F3 tornado which caused severe damage in portions of Falls County near Bruceville-Eddy and Lake Belton. Another tornado, rated an F0, touched down near Stillhouse Dam and was incorrectly claimed as the Jarrell tornado due to its close proximity from the F5 tornado's path. This tornado was also subject of a famous image.[7]

Shortly thereafter, the supercell began to move slightly westward towards Jarrell and Salado, while continuing to show signs of rapid, low-level rotation. This would result in another tornado warning being issued by the National Weather Service in Austin/San Antonio for Williamson County, including Jarrell, at 15:30 CDT (22:30 UTC), in response to the storm's approach to the town. The warning was in effect for a duration of one hour, and local warning sirens in the town went off an estimated 10--12 minutes before the impact.[5][8][9] Multiple short-lived, small, and rope-like funnel clouds preceded the Jarrell tornado; and despite being theorized and commonly accepted as being separate tornadoes, there is a possibility that these were part of it.[7]

Tornado summary

[edit]Formation, track towards Jarrell

[edit]

The tornado officially touched down within the Williamson County line 3 miles (4.8 km) north of Jarrell as a faint, rope-shaped funnel swathed in large amounts of dust. The tornado began to undergo a dramatic intensification as it took on the shape of a "dead man walking", with multiple subvortices creating a human-like shape at approximately 3:40 p.m.[4][7] This was preceded by the formation of multiple short-lived, small, and rope-like funnel clouds that are theorized and commonly accepted as separate events apart from the Jarrell tornado.

Traffic along Interstate 35 came to a stop as the tornado descended nearby.[10] The Texas Highway Patrol also stopped traffic on both sides of the interstate under the expectation that the tornado would cross the highway; it ultimately moved parallel to Interstate 35,[11] and no injuries were reported on the highway.[12]

Tracking south-southwest, the tornado quickly intensified and grew in width.[13] The exact size of the tornado was hard to pinpoint, as F5 damage was first recorded as it widened.[12] It is unusual, as F5 damage was documented relatively early into its lifespan and retained until almost the end of the tornado. Its intense winds scoured the ground, vegetation and stripped pavement from County Roads 308, 305, and 307;[14] the thickness of the asphalt pavement was roughly 3 inches (7.6 cm). A culvert plant at the corner of Country Roads 305 and 307 collapsed. Nearby, a similar plant and a mobile home sustained some damage, with the latter struck by a 2×4 piece of lumber.[15]

Some of the most extreme damage at this location was inflicted to a small metal-framed recycling plant that was directly hit and destroyed, with only several twisted and bent metal beams remaining.[4] Multiple people were sheltering in a mobile home far south of the recycling plant,[16] but later decided to evacuate to a frame house to take cover. The frame house was directly hit by the tornado moments later, killing everyone inside. The tornado narrowly missed the mobile home that they were originally taking shelter inside, leaving it with minor damage. The mobile home would have likely saved their lives.

Impact at Double Creek Estates

[edit]

The tornado turned slightly, entering the Double Creek Estates at high-end F5 intensity. It grew to its maximum width, estimated to be around 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km). Post-event surveys and eyewitness accounts have suggested that the tornado began to slow its pace, which contributed to the extremely violent damage observed there.[12][17] The tornado immediately began to destroy structures and homes as it hit multiple smaller streets at the northeastern edge of the Estates. The exact time of this is unknown, but timekeeping devices from remaining debris and synced videos have shown that this most likely happened at 3:48 p.m.[14][12]

The entire Double Creek Estates was subjected to extreme winds for three minutes due to the "stalling" pattern of the tornado, which likely exacerbated the damage. Multiple well-built homes on Double Creek Drive were completely swept away and clean slabs were left with lack of any large debris.[18][12] Foundations in the direct path of the tornado had all of their plumbing and sill plates ripped away. Some of the foundations were partially scoured.[19][20][17] The tornado was heavily documented during this phase, and was most likely at its most visible point in its lifespan. Grassy fields in this area also sustained extreme ground scouring of up to 18 inches (46 cm).[21] As a result of this, the path was heavily studied due to its visibility and scarring into the ground.[21][12]

Cars were picked up by the tornado and mangled beyond recognition or torn apart, and at least six recognizable cars were found over 300 yards (270 m) away but crushed and covered in mud. Many were never recovered, and are presumed to have been "ground up" inside the debris ball. All trees in the subdivision were completely debarked, with one small tree documented to have had an electrical cord pierced through its trunk.[12]

Three entire families were killed in this area: the Igo family (five members), the Smith family (three members) and the Moehring family (four members).[22]

Damage to Jarrell

[edit]

Thirty-eight structures were obliterated in the Double Creek Estates.[12] Three businesses adjacent to Double Creek Estates were also destroyed. In total, the tornado dealt $10–20 million in damage to the neighborhood. The tornado turned slightly towards the south-southwest after traversing Double Creek Estates.[23][12]

The tornado then traversed County Road 396, inflicting F4+ damage (area was never accurately surveyed), destroying structures in its path and denuding trees. It tracked through a field, causing deep ground scouring before Land Cemetery Road, destroying a cemetery in the process at an unknown intensity.[24]

Dissipation

[edit]The tornado then again crossed County Road 305.[25][12][26] It began to track parallel to Spears Ranch Road, before entering into cedar forest and beginning to rapidly weaken. It hit a few more houses at an unknown intensity, and hit Appaloosa Cove Road before taking on a "pencil" shape and finally dissipating.[27] The NCEI concluded that it had lifted at 3:53 p.m. after remaining on the ground for 13 minutes and traversing 5.1 miles (8.2 km).[27][12]

The path itself was extremely unusual, as it tracked southwestward, instead of northeastward, which is the path that tornadoes normally take. Other tornadoes in the outbreak also took southerly paths.[12]

Aftermath

[edit]Within minutes after the tornado's impact, emergency management, police, and other volunteers began search-and-rescue operations in Jarrell. Numerous different agencies assisted in the search-and-rescue process, including the Texas Department of Public Safety Police, Texas National Guard, and other smaller agencies. Relief operations, which covered 211 homes and persons damaged or wounded in the tornado, cost an estimated $250,000; community donations covered at least $200,000 of the expenses.[28]

The tornado knocked out power in Jarrell,[clarification needed] effectively stunting communications between EMS and residents. Cell phones were not functional, and the loved ones of residents became increasingly concerned due to an inability to communicate.[29] Despite this, emergency services were quick to arrive in Jarrell, and the damage was so intense that they almost drove past Double Creek Estates, unaware that houses had stood there. The Double Creek Estates subdivision quickly became the focal point of search-and-rescue and recovery efforts, which were aided by civilians and volunteer workers.[29]

In the six days following the event, the Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research (OOTCFMSASR) conducted multiple surveys from the air and on the ground to survey the track of the tornado and the damage caused by it. The Texas branch of the Civil Air Patrol also helped, and in the end the tornado garnered an F5 rating, which was challenged by the NIST.[4]

Support came in from all over the country, and millions of dollars were donated to aid Jarrell. Texas Governor George W. Bush visited Jarrell days after the tornado and stated that the "damage was mind-boggling."[30]

The Jarrell Volunteer Fire Department organized a temporary morgue. Although a death toll of 30 people was initially reported, that figure was later revised to a final tally of 27.[28]

Rebuilding

[edit]County Road 305 and Double Creek Drive have been repaved multiple times since the event. Many businesses have rebuilt and returned to normalcy, while other lots that were completely wiped away in the tornado were abandoned.

A memorial park, which includes twenty-seven trees to commemorate the victims and two baseball fields, was built on land donated by relatives of the Igo family, who all perished in the tornado. Many residents who had initially remained in the aftermath of the tornado later moved away due to rebuilding costs and other factors. Many residents did stay, although the population has not grown much since the event.[31]

Fatalities

[edit]

Out of the 131 residents who lived in or near Double Creek Estates, 27 were killed. The remains of these people were found at over 30 locations, and the majority of the deaths were reported in the[32] Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report as being caused by bodily and head trauma and one fatality was reported to have been caused by asphyxia. Bodily remains were later found at 30 locations, and the physical trauma inflicted on some of the tornado victims was so extreme that first responders reportedly had difficulty distinguishing human remains from the remains of animals at the sites, as the remains were reportedly "ground up" in the winds of the tornado.[33][20]

The sheer strength and intensity of the tornado, as it was in Jarrell, gave the people in its direct path little time to get to safety. Most of the homes that were located in Double Creek Estates at the time were constructed on a slab foundation and lacked of a basement. Up to nineteen people had sought refuge in a single storm cellar.[34]

Many residents of the Double Creek Estates had still followed the recommended safety procedures, but were still killed because of the strength of the tornado.[35] Some people had chosen to evacuate ahead of the tornado, which may have saved lives. Despite the near-complete destruction of houses on the edge of the tornado, some walls were left standing, protecting several residents.[36] One survivor holed up in a bathtub and was flung several hundred feet from her house onto a road.[35][12]

Around 300 cattle grazing in a nearby pasture were killed and some were found 0.25 miles (400 m) away. Hundreds of these bodies were found dismembered, lacking limbs, decapitated or skinned.[7][23]

13 people were reported to have been admitted to a hospital after the event, and one person died there. Most of the wounded had abrasions and lacerations due to debris from the tornado.[23] Nine families in Jarrell had more than one member die in the tornado, and the youngest victim was five years old.[23]

After the tornado, multiple residents of Jarrell were interviewed about the tornado and the actions that they took. Many said they were aware of the tornado warnings, and the majority said that they first learned of the warnings through commercial television.[37]

Due to the slow movement and high visibility of the tornado, most of the residents interviewed said they watched the approach of the tornadoes prior to taking shelter. Most said they knew to go to the center of their houses, to avoid staying in mobile homes, and to seek shelter rather than trying to flee the tornadoes. These actions saved lives, but in the case of the Jarrell tornado were unable to prevent fatalities.[37]

Documentation

[edit]The tornado was heavily documented during its lifetime, making it a focal point of research for the NWS and other weather agencies. Multiple videos exist of the tornado, showing the fast rotation and heavy debris cloud that engulfed the tornado during its maximum strength.

"Dead Man Walking" photograph

[edit]

The Jarrell tornado was the subject of one of the most famous pieces of tornado media ever taken, now known as the "Dead Man Walking". Scott Beckwith took the famous photograph, which has become notorious for closely resembling the grim reaper.[38]

The image consists of the tornado, shrouded in debris, with the main vortex and an adjacent subvortice making "leg" shapes near the bottom of the tornado, giving it the appearance of a giant silhouette walking across the ground. A third subvortice separate from the main funnel is also seen, resembling that of the blade of a reaper's scythe.[39] The image has been widely called an example of pareidolia.[40] It is one of 8 photographs taken in a sequence as the tornado grew in size.

The photo has received international mainstream attention and has gained it and many other similar tornadoes the nickname of the "Dead Man Walking tornado".[2] Many other spin-off images have been produced, including a photograph of the 2013 El Reno tornado. "Dead Man Walking" tornadoes are now generally referred to multi-vortex tornadoes with "legs", but the Jarrell tornado helped popularize the term.[39]

Videos

[edit]Multiple famous videos have been taken of the tornado, including one by photojournalist Scott Guest, who captured the earlier tornadoes and main tornado forming.[41]

Other media

[edit]In the aftermath of the tornado, multiple books and publications were released, which detail the stories of survivors. A documentary, titled "The Jarrell Tornado: 20 Years Later" was released in 2017, and shows footage from Scott Guest and Tim Marshall, both of whom were photographers and videographers in Jarrell during the event.[42]

Damage

[edit]This section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. This template was placed by Sir MemeGod :D (talk - contribs - created articles) 03:03, 8 August 2024 (UTC). If this section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Sir MemeGod (talk | contribs) 5 hours ago. (Update timer) |

Structural

[edit]The tornado caused widespread damage to structures, and destroyed an estimated 40 family residences.[43] Of these estimated 40 homes, multiple were completely swept off their foundations as a result of the wind.[44] Many of the structures that were swept away were located in the double Creek Estates.

Monetary

[edit]The Jarrell tornado damage was classified as F5 severity throughout most of the tornado's path.[45] Approximately $40 million in damage was inflicted upon property with another $100,000 inflicted upon crops.

Reactions

[edit]Then-governor of Texas George W. Bush[30] declared Williamson County a disaster area, and during a visit to Jarrell on May 28, stated that "it was the worst tornado I've ever seen".[46] U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison also visited Jarrell and Cedar Park. Bush later requested federal aid for Williamson and Bell counties with support from Hutchinson.[46]

The Federal Emergency Management Agency elected not to provide federal aid, citing the contributions from private and state sources. Instead, the Small Business Administration and U.S. Department of Agriculture made available loans for the rebuilding of homes, farms, and ranches.[46]

Between May 29 and June 1, the Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research carried out aerial and ground surveys of the tornadic damage in Texas in coordination with the Texas Wing Civil Air Patrol.

Case studies

[edit]Multiple in-depth studies have been conducted on the tornado, which detail what happened on May 27, and what caused the outbreak and subsequent Jarrell tornado to unfold.

American Meteorological Society (AMS)

[edit]The American Meteorological Society (AMS) conducted a case study on the event.[47] It discussed the meteorological conditions that caused the event and the significance of the Jarrell tornado.[47]

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

[edit]

A case study and critique was published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which covered the structural damage caused by the tornado and the track that it left. The NIST also published a detailed critique of the Fujita Scale as a direct result of the Jarrell tornado, which was at the time rated an F5. The critique stated that:

"We ascribe the NWS rating to the failure of the Fujita tornado intensity scale to account explicitly for the dependence of wind speeds causing specified types of damage or destruction upon the following two structural engineering factors: (1) quality of construction, defined as degree of conformity to applicable standards requirements, and (2) the basic design wind speed at the geographical location of interest."[19]

The NIST had claimed that the Fujita Scale failed to account for critical pointers in the assessment of the Jarrell tornado. The case study concluded that some of the homes at Double Creek Estates did have small structural integrity issues,[4] which includes factors such as a lack of sufficient anchor bolts and steel straps in the house foundations.[4] After the critique was published, the rating was kept as an F5.

University of Wisconsin-Madison

[edit]The University of Wisconsin-Madison also published a case study on the event, authored by Andrew Mankowski, which detailed the weather conditions that caused the tornado to form and how it became as violent as it was. The study said that:

"From a synoptic view the main feature was a cold front pushing its way south into Texas. Frontogenesis helped aid in forcing some of the upward vertical motions. From the Gulf of Mexico came a southerly low-level jet bringing warm moist air. This warm moist air from the LLJ helped destabilize the air. The air was already highly unstable with CAPE values reaching 6,000 J/kg."[48]

According to Mankowski, the CAPE values in the atmosphere at the time were extremely unstable, contributing to directional shear which formed the supercells. This caused the violent rotation that eventually produced the Jarrell tornado, and the subsequent strength of the tornado.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

[edit]The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which is a U.S. government-affiliated disease control group, produced a study on the casualties of the tornado, which included in-depth explanations of the injuries sustained to the bodies of victims, lengths of hospital stays, among other things. The study and survey concluded that:

"A total of 33 persons presented to six area hospitals for treatment of injuries sustained directly or indirectly by the three tornadoes. Of these 33 persons, 13 (39%) had multiple diagnoses. The categories of injuries included lacerations (18 {55%}), contusions (15 {46%}), abrasions (10 {30%}), strains/sprains/muscle spasms (six {18%}), fractures (two {6%}), penetrating wound (one {3%}), and closed-head injury (one {3%}). The median age of the injured persons was 38 years (range: 1-75 years)."[49]

The case study had also noted the lack of shelters causing multiple of the deaths, and recommended that more storm shelters be installed in Jarrell.[49] Had shelters been implemented before the tornado, many more lives may have been potentially saved, and the tornado showed the importance of storm shelters.[49]

Other studies

[edit]Many other groups and organizations did small case studies and surveys in the wake of the tornado, which include the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)[50] and the Regional and Mesocale Meteorology Branch (RaMMB).[51] A small case study by the NOAA had concluded that the Emergency Alert System (EAS) was not activated in a timely manner to warn about the tornado.[23] Many warning systems had also failed, and the study recommended that emergency alerts and tornado warnings be issued earlier.[23]

Gallery

[edit]The tornado was one of the most well-documented F5 tornadoes, and many photos and videos exist of the tornado as the event unfolded, and the respective aftermath:

Damage

[edit]Tornado

[edit]See also

[edit]- 1999 Bridge Creek–Moore tornado, another extremely powerful and violent F5 tornado that struck Oklahoma in 1999

- 2007 Elie tornado, another F5 tornado in 2007 with slow movement and an unusual path

- 2011 Smithville tornado, an fast-moving EF5 tornado from the 2011 Super Outbreak that caused exceptionally extreme damage and debris granulation comparable to this tornado

- 2011 Joplin tornado, an EF5 tornado in 2011 that caused similar damage patterns

References

[edit]- ^ Osborn, Claire; Easterly, Greg; Ward, Pamela (May 28, 1997). "Nearly destroyed in '89, Jarrell is slammed again". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A10. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- p. A1 Archived 2024-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- p. A10 Archived 2024-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Patterson, Kaley PattersonKaley (2024-04-15). "Ever Heard of the 'Dead Man Walking' Tornado?". KLAW 101. Archived from the original on 2024-05-12. Retrieved 2024-05-12.

- ^ "'Hold on tight': 25 years since the Jarrell, TX tornado outbreak". KXAN Austin. 2022-05-23. Archived from the original on 2024-05-10. Retrieved 2024-05-10.

- ^ a b c d e f Texas Event Report: F5 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "The Tornadoes of May 27, 1997". National Weather Service Fort Worth, Texas. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ Corfidi, Stephen F. (July 1998). Some Thoughts On the Role Mesoscale Features Played in the 27 May 1997 Central Texas Tornado Outbreak. 19th Severe Local Storms Conference. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Storm Prediction Center. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "May 1997 Tornado Outbreak" (PDF). New Braunfels, Texas: National Weather Service. May 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Henderson et al. (1998), p. A9.

- ^ Henderson et al. (1998), p. 1.

- ^ Harmon, Dave (May 28, 1997). "'Like a war zone'". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A12. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tornadoes kill 30 in Central Texas". El Paso Times. El Paso, Texas. Associated Press. May 28, 1997. p. 1A. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Tornado Archive Data Explorer - Tornado Archive". tornadoarchive.com. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ "The Tornadoes of May 27, 1997". Jarrell-Tornado-Anniversary. Fort Worth, Texas: National Weather Service Fort Worth/Dallas, TX. Archived from the original on April 4, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Texas Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original on April 2, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "May 1997 Tornado Outbreak" (PDF). New Braunfels, Texas: National Weather Service. May 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "Stormtrack Magazine: Jarrell, Texas Tornado Expanded Edition" (PDF). Stormtrack. 21 (1). 1997. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2024-06-20.

- ^ a b Verhovek, Sam Howe (May 29, 1997). "Little Is Left in Wake of Savage Tornado". The New York Times. New York. p. A1. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ "May 1997 Tornado Outbreak" (PDF). New Braunfels, Texas: National Weather Service. May 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Phan, Long T.; Simiu, Emil (1998-07-01). "Fujita Tornado Intensity Scale: A Critique Based on Observations of the Jarrell Tornado of May 27, 1997 (NIST TN 1426)". NIST. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ a b "May 27, 1997 — the Jarrell, Texas Tornado". 24 November 2012. Archived from the original on 8 January 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ a b "May 1997 Tornado Outbreak" (PDF). New Braunfels, Texas: National Weather Service. May 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Rucker, Hanna (May 25, 2022). "Three families killed in the 1997 Jarrell tornado are buried together in Georgetown". kvue.com. KVUE. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Storm Data" (PDF). Storm Data. 39 (5). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. May 1997. ISSN 0039-1972. Retrieved April 7, 2021 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Tornado Archive Data Explorer - Tornado Archive". tornadoarchive.com. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ Harmon, Dave (May 28, 1997). "'Like a war zone'". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A12. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ TX, NWS Austin/San Antonio, TX and NWS Fort Worth/Dallas (2022-05-19). "May 27, 1997 Central Texas Tornado Outbreak". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Archived from the original on 2024-06-04. Retrieved 2024-07-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "May 1997 Tornado Outbreak" (PDF). New Braunfels, Texas: National Weather Service. May 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "Article clipped from Austin American-Statesman". Austin American-Statesman. 1997-05-29. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2024-05-17. Retrieved 2024-05-17.

- ^ a b "First responders reflect on recovery efforts during 1997 Jarrell tornado". kvue.com. 2022-05-24. Archived from the original on 2024-08-03. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ a b "After an F-5 tornado hit Jarrell in 1997, then-Gov. George W. Bush visited to survey the damage". kvue.com. 2022-05-24. Archived from the original on 2024-08-03. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ "May 27, 1997 — the Jarrell, Texas Tornado". 24 November 2012. Archived from the original on 8 January 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Schuman, Shawn (November 23, 2023). "May 27, 1997 — The Jarrell, Texas Tornado". stormstalker.wordpress.com. Wordpress. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Rucker, Hanna (May 25, 2022). "Three families killed in the 1997 Jarrell tornado are buried together in Georgetown". kvue.com. KVUE. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Beach, Patrick (May 29, 1997). "Jarrell's toll 27; 23 still missing". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A21. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- p. A1 Archived 2024-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- p. A21 Archived 2024-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Beach, Patrick (June 1, 1997). "Their roots held". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A20–A21. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- p. A1 Archived 2024-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- p. A20 Archived 2024-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- p. A21 Archived 2024-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Storm Data" (PDF). Storm Data. 39 (5). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. May 1997. ISSN 0039-1972. Retrieved April 7, 2021 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "The central Texas tornadoes of May 27, 1997". repository.library.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 2024-05-17. Retrieved 2024-05-17.

- ^ "The TIME Vault: June 9, 1997". TIME.com. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-29.

- ^ a b Edge, The Professor On (2020-06-14). "(A preview of) Meteorology and Myth Part VII: "The Dead Man Walking"". From Equatorial Icecaps to Polar Deserts. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2023-06-29.

- ^ "The TIME Vault: June 9, 1997". TIME.com. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-29.

- ^ "In his own words, KVUE photojournalist recalls 1997 Jarrell tornado and how it affected him". kvue.com. 2022-05-27. Archived from the original on 2022-10-26. Retrieved 2024-05-11.

- ^ KVUE (2017-05-27). Jarrell Tornado: 20 years later | KVUE. Archived from the original on 2024-06-02. Retrieved 2024-06-02 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Tornado Jarrell Texas 1997". NIST. 2011-05-27. Archived from the original on 2024-05-13. Retrieved 2024-08-08.

- ^ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "A list of the top 10 worst tornadoes in Texas history". www.weather.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-05-02. Retrieved 2024-08-08.

- ^ Osborn, Claire; Easterly, Greg; Ward, Pamela (May 28, 1997). "Nearly destroyed in '89, Jarrell is slammed again". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A10. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- p. A1 Archived 2024-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- p. A10 Archived 2024-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "'Hold on tight': 25 years since the Jarrell, TX tornado outbreak". KXAN Austin. 2022-05-23. Archived from the original on 2024-05-10. Retrieved 2024-05-11.

- ^ a b Houston, Adam L.; Wilhelmson, Robert B. (2007-03-01). "Observational Analysis of the 27 May 1997 Central Texas Tornadic Event. Part II: Tornadoes". Monthly Weather Review. 135 (3): 727–735. Bibcode:2007MWRv..135..727H. doi:10.1175/MWR3301.1. ISSN 1520-0493. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ Andrew, Mankowski. "University of Wisconsin Case Study Jarrell 1997" (PDF). The Jarrell Tornado of May 27, 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 3, 2024. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Tornado Disaster -- Texas, May 1997". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2024-05-19. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ Houston, Adam L.; Wilhelmson, Robert B. (2007-03-01). "Observational Analysis of the 27 May 1997 Central Texas Tornadic Event. Part II: Tornadoes". Monthly Weather Review. 135 (3): 727–735. Bibcode:2007MWRv..135..727H. doi:10.1175/MWR3301.1. ISSN 1520-0493. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ "RaMMB2". Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to 1997 Jarrell tornado at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 1997 Jarrell tornado at Wikimedia Commons

Sources

[edit]- Henderson, James H.; Hakkarinen, Ida M.; Lerner, William H.; McLaughlin, Melvin R.; Looney, James M.; McIntyre, E. L.; Peters, Brian E.; Trainor, Marilu; Paz, Enrique; Kolavic, Shellie Ann; Zane, David; Phan, Long T. (April 1998). The Central Texas Tornadoes of May 27, 1997 (PDF) (Service Assessment). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Tornado Disaster -- Texas, May 1997 (Report). November 14, 1997.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - The central Texas tornadoes of May 27, 1997 (Report). April 1998.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.